Background

I know from personal experience that low back pain is a common and debilitating condition. Fortunately most acute episodes of low back pain resolve spontaneously within a few weeks or months, and only require advice to maintain daily activities. However some episodes can go onto chronic low back pain which may never fully resolve. This blog focuses mostly on this chronic category with a mix of some personal lessons plus some reviews of the literature, outlining what is known and what still needs to be subject to control trials.

Every few years I had experienced about an acute low back pain with right-sided sciatica but these generally resolved within a few weeks or months and required nothing further than staying active. However a few years ago I experienced an episode which did not resolve but plateaued and eventually began to get worse. I saw a neurosurgeon: my MRI showing several disc lesions (but we know that there’s a poor correlation between symptoms and disc lesions), so my neurosurgeon wisely organised for a steroid and local anaesthetic injection into the likely culprit disc -which gave me the first, albeit temporary, pain relief in 18 months, but also suggested surgery might help.

The following are my lessons from my rehabilitation period following a microdiscectomy – which provided sufficient relief from the sciatica to enable me to restart many activities, but with strength and mobility deficits to overcome. Activity and exercise is vital, and as many folks say “motion is lotion.” A Cochrane review and overview of reviews found that “exercise therapies probably provide a small to medium reduction in pain intensity”. [Rizzo; Geneen] But that activity should also involve “good” movements as poor posture and poor movements can make the pain worse. However, that good movement also requires adequate strength and mobility, as I found during my recovery.

Over the 18 months of my pain I have become less less able to walk and stand and consequently had reduced strength and mobility. However, to enable sufficient walking required re-strengthening of my legs – particularly my gluteals. In addition, my left calf was weaker (spotted by my alert physiotherapist) causing pronation and Achilles tendonopathy. Finally, my hip extension had become limited causing some difficulty walkingwell, and required some mobility work.

Five Lessons

So my current (but ever changing!) mental model is that reducing low back pain requires being capable of maintaining daily activities, with good movement and posture, which in turn may require correction of relevant strength or mobility and movement deficits. So my five lessons – some from the literature; some from personal experience – in order are:

1. Stay active. In particular try maintain normal-ish daily activities – within sensible limits that avoids complete rest but also excess active that triggers fatigue and avoidance. Particularly useful are short regular walks, preferably daily. The advice to stay active is supported by multiple trials[Rizzo 2025; Geneen 2017] and walking specifically by the recent WalkBack trial [Pocovi 2024] showed significant decreases in recurrence rates of low back pain with a simple program of advice to walk regularly. Regular walking and “normal activity” are probably sufficient for simple acute low back pain episodes most of which spontaneously resolve within weeks or months (as with my earlier episodes). However, for recurrent or chronic low back pain some additional recommendations may be warranted – hence 4 more “lessons”.

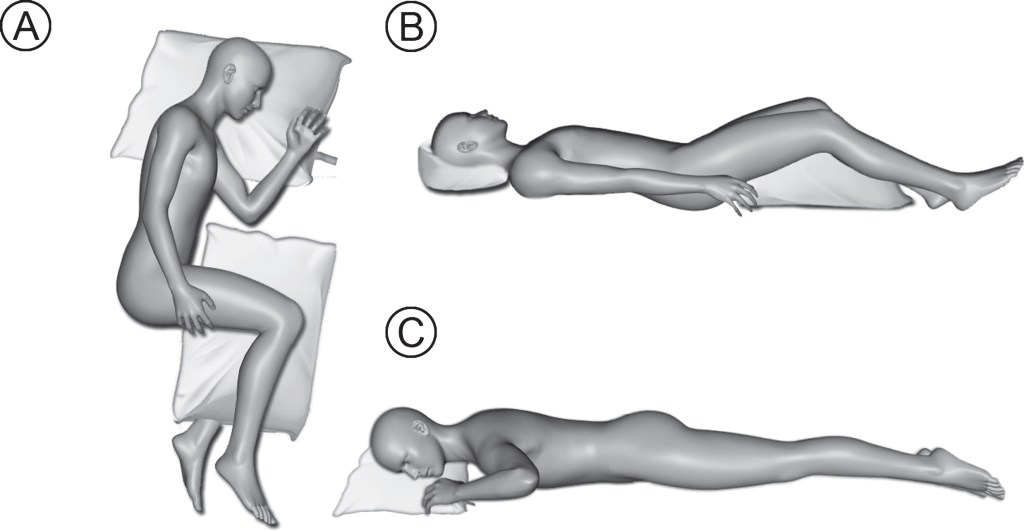

2. Find good sleeping positions. We spend roughly a third of our day sleeping, so it can have considerable influence on the progression or regression of low back pain. Unfortunately, this crucial area has very limited controlled trial evidence. I could find only one small pilot study [Desouzart 2015] which randomised 20 subjects to usual sleeping or advice – as illustrated in the Figure below – to control or to preferably use pillows to support either side sleeping or back sleeping (A & B in Figure). The experimental group had significantly less low back pain at four weeks. That’s possibly an important finding but this simple intervention clearly warrants confirmation in larger trials.

Fig.1 Recommended sleeping positions and pillow orientation (Recommended A – lateral position with pillow between knees; B – supine sleep position with pillow under knees). Not recommended – prone sleep position (C –prone sleep position). https://journals.sagepub.com/cms/10.3233/WOR-152243/asset/f2bae197-3916-4910-94df-a512f5c9b224/assets/graphic/10.3233_wor-152243-fig1.jpg

Prior to my operation, I had learned the value of using a pillow between my knees (see Figure position A) but subsequently added a very small pillow between my lower ribs and pelvis to help keep my spine more level. Furthermore, concerned about possible shoulder pain, I learned to sleep on my back – at first just with daytime naps and later adding it as an alternative position to not sleeping. This has definitely reduced my morning pain and stiffness.

I have listed “sleeping position” second, as it helped me considerably, and is a very simple and low cost addition to staying active; but it is sadly under-researched.

3. Targeted strength & stability training. Adequate strength and stability are important to be able to walk well and to maintain normal activities with a well supported spine. The most common program focuses are: “core strength“ and strength of the legs, particularly the gluteals, for maintaining standing and walking stability and balance. There are several good trials indicating that core strengthening in particular has a modest effect on reducing low back pain and disability [Fernandez-Rodriguez 2022]. There are many variants of the set of core exercises with the most famous perhaps being the McGill big three: the “bird dog”, “side plank”, and “curl up”. Some other muscles may also require strengthening, but are more likely to vary across individuals.

My reduced activity in the 18 months of low back pain had led to weakening of several muscles, reducing my ability to walk, and carry out normal activities. So some strengthening – devised with my physiotherapist – was a useful complement. I would first note though the importance of carrying out exercises correctly. Initially core exercises such as the “dead bugs” (lying on my back with arms and legs in the air) made my back worse; that was because I arched my back, rather than correctly holding the low back steady or flat during the exercise. I also had weakened gluteals needed for walking stability, and finally a left Achilles tendinopathy lead my physiotherapist to recognise my much weaker left calf, which needed strengthening. It took 4-6 weeks to note much change, and I continue to do these.

4. Improved Mobility. Moving well in daily activities requires a minimum degree of mobility of many joints. Chronic and recurrent low back pain such as mine can lead to reductions in mobility that will need to be addressed as part of the support for staying active.

My 18 months of low back pain and subsequent surgery led to several decreases in mobility that were asymmetric. My back movements had become limited and my right hip movements were greatly restricted and both of these interfered with walking and other activities. Crucially, my physiotherapist noted how much tighter my right sided back muscles (quadratus lumborum etc) were than my left. This problem probably developed pre-op, but now left me with a negative cycle of pain->tightness->more pain, etc. That insight triggered an important element of my rehabilitation program: a set of mobility exercises but particularly focused on my right back and hip.

Mobility is more than stretching. And indeed stretching alone appears to have minimal effects in reducing pain and disability in low back pain (though Yoga does have a modest effect [Wieland 2022]). Mobility can be improved by relaxation or by movements through a range of motion, without stretching. To illustrate this, one small trial [Ahmadi 2020] of five “Feldenkrais exercises” for back pain mostly focused on slow, small pelvic movements (similar to a “pelvic clock”). The intervention group not only had reduced pain and disability, but also increased range of motion – without any stretching, only the gentle movements. Similar mobility “exercises“ are also done in some other programs, such as Pilates (which includes a “pelvic clock” as well as core strengthening).

5 Good movement & posture. Given about 2/3rds of the non-sleeping part of our day will involve in some activity, such as standing, sitting, or walking, then paying attention to how common activities influence low back pain would seem logical. Certainly my own experience was that finding better ways to sit, stand, and walk “well” were important for reducing my low back pain and disability.

I usually spend at least half an hour a day bent over a kitchen bench, but the bending made my back pain worse. Learning to “hip hinge” well has not just alleviated that pain, but I now find bending “well” (from the hips; relaxed straight lower back) can actually reduce my back pain.

Unfortunately there are few trials of postural training for treating back pain. However, one large UK trial (579 patients) found that Alexander Technique lessons had a greater impact than other treatments (massage; exercise) and that improvement was not only sustained, but increased by 12 months [Little 2008], and were more effective than exercise (mostly walking) and massage. The apparent effect size was substantial: “The effect of 24 lessons in the Alexander technique was greater at one year than at three months, with a 42% reduction in Roland disability score and an 86% reduction in days in pain compared with the control group”.

The Alexander technique is complex, but in short focuses on a maintaining a “release” (the minimum necessary tension) of the neck and low back in activities – and these are connected: releasing the neck also releases the lower back and vica versa. Notably, Alexander lessons have no strengthening or stretching elements. Hence, combining Alexander with other strengthening and/or mobility may provide additive benefits (one small pilot has examined this – Little 2014).

Combining elements

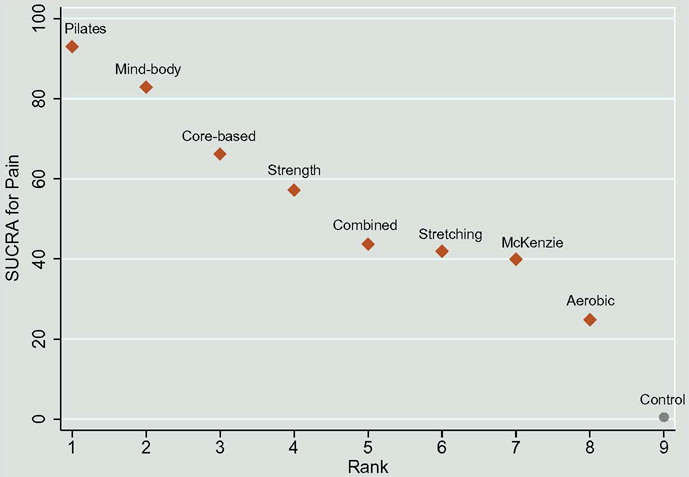

Some interventions focus on a single approach, but many use some combination, usually strength and mobility. For example, a network meta-analysis of 118 controlled trials [Fernández-Rodríguez 2022] found a variety of exercises were effective, but ranked Pilates (24 trial groups) highest (see Figure). “Pilates” (named after its inventor) involves a variety of exercises, but notably combines core strength training (exercises similar to glute bridges, curl ups, and “dead bugs”) and mobility activities (such as “pelvic clock”). Note that some of the Pilates effects may be via reductions in fear of movement[Wood 2023], but that is probably true of most activity interventions for low back pain – they act as “behavioural experiments” that increase the range of motion and activity.

FIGURE 4. (From Fernández-Rodríguez 2022) Ranking for each intervention on pain (SUCRA: surface under the cumulative ranking curve)

In summary, my experience with chronic low back pain has been helped by the good evidence from trials for core strengthening and mobility, but also by interventions with fewer trials, such as sleeping position and postural (eg Alexander) training. Given sleeping and nonsleep activities will consume much more time than any exercise program, using that time well seems an obvious target for further study.

To find optimal combinations, priorities for future research might include factorial studies which include these elements. In particular, changing sleeping position is such a simple low cost intervention, it could be included as a factor in future trials of other interventions.

References

Rizzo RR, Cashin AG, Wand BM, Ferraro MC, Sharma S, Lee H, O’Hagan E, Maher CG, Furlan AD, van Tulder MW, McAuley JH. Nonpharmacological and non-surgical treatments for low back pain in adults: an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2025 Mar 27;3(3):CD014691. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD014691.pub2. PMID: 40139265; PMCID: PMC11945228.

Geneen LJ, Moore RA, Clarke C, Martin D, Colvin LA, Smith BH. Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Apr 24;4(4):CD011279. doi: 0.1002/14651858.CD011279.pub3. PMID: 28436583; PMCID: PMC5461882.

Pocovi NC, Lin CC, French SD, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of an individualised, progressive walking and education intervention for the prevention of low back pain recurrence in Australia (WalkBack): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2024 Jul 13;404(10448):134-144. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00755-4. Epub 2024 Jun 19. PMID: 38908392.

Desouzart G, Matos R, Melo F, Filgueiras E. Effects of sleeping position on back pain in physically active seniors: A controlled pilot study. Work. 2015;53(2):235-40. doi: 10.3233/WOR-152243. PMID: 26835867.

Fernández-Rodríguez R, Álvarez-Bueno C, Cavero-Redondo I, Torres-Costoso A, Pozuelo-Carrascosa DP, Reina-Gutiérrez S, Pascual-Morena C, Martínez-Vizcaíno V. Best Exercise Options for Reducing Pain and Disability in Adults With Chronic Low Back Pain: Pilates, Strength, Core-Based, and Mind-Body. A Network Meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2022 Aug;52(8):505-521. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2022.10671. Epub 2022 Jun 19. PMID: 35722759.

Khaledi A, Gheitasi M. Isometric vs Isotonic Core Stabilization Exercises to Improve Pain and Disability in Patients with Non-specific Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Anesth Pain Med. 2024 Feb 15;14(1):e144046. doi: 10.5812/aapm-144046. PMID: 38725921; PMCID: PMC11078224

Wood L, Bejarano G, Csiernik B, Miyamoto GC, Mansell G, Hayden JA, Lewis M, Cashin AG. Pain catastrophising and kinesiophobia mediate pain and physical function improvements with Pilates exercise in chronic low back pain: a mediation analysis of a randomised controlled trial. J Physiother. 2023 Jul;69(3):168-174. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2023.05.008. Epub 2023 Jun 3. PMID: 37277290.

Wieland LS, Skoetz N, Pilkington K, Harbin S, Vempati R, Berman BM. Yoga for chronic non-specific low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022 Nov 18;11(11):CD010671. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010671.pub3. PMID: 36398843; PMCID: PMC9673466.

Ahmadi H, Adib H, Selk-Ghaffari M, Shafizad M, Moradi S, Madani Z, Partovi G, Mahmoodi A. Comparison of the effects of the Feldenkrais method versus core stability exercise in the management of chronic low back pain: a randomised control trial. Clin Rehabil. 2020 Dec;34(12):1449-1457. doi: 10.1177/0269215520947069. Epub 2020 Jul 29. PMID: 32723088.

Little P, Lewith G, Webley F, Evans M, Beattie A, Middleton K, Barnett J, Ballard K, Oxford F, Smith P, Yardley L, Hollinghurst S, Sharp D. Randomised controlled trial of Alexander technique lessons, exercise, and massage (ATEAM) for chronic and recurrent back pain. BMJ. 2008 Aug 19;337:a884. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a884. PMID: 18713809; PMCID: PMC3272681.

Little P, Stuart B, Stokes M, Nicholls C, Roberts L, Preece S, Cacciatore T, Brown S, Lewith G, Geraghty A, Yardley L, O’Reilly G, Chalk C, Sharp D, Smith P. Alexander technique and Supervised Physiotherapy Exercises in back paiN (ASPEN): a four-group randomised feasibility trial. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2014 Oct. PMID: 25642555.